Research shows us the benefits of music for language and literacy as well as self-regulation and mental health. But does how we teach music matter?Musician and early childhood teacher, AMY ROTHE explores different methods of teaching music to young children, such as the Suzuki method, and delves into her personal teaching experiences and practice.

When you read the phrase ‘early childhood music’ what pops into your mind? Is it an image of a pre-schooler propped up on cushions learning the piano? Is it a group of children singing nursery rhymes and finger songs with their educator? Is it a three year-old dancing and singing along to the television? Early childhood music is such an expansive phrase that encompasses all of these things and more. There is a plenitude of methods and theories when it comes to teaching or using music in the early years but in the realm of early childhood education, someone needs to ask the question, ‘Does it matter’? Yes it matters! Music matters.

Research shows us the benefits music has on language and literacy as well as self-regulation and mental health. Does delivery of music education matter? And do different approaches have the same benefits? For example, a classical-trained musician teaching a child an instrument has a vastly different pedagogical approach to an early childhood teacher using music in a transition or in group time. So, what does research tells us about the benefits of music in early childhood education and the way the music is delivered to the child?

One-on-one learning

There are endless ways for children to learn about music, one specific approach is using one to one instruction with a teacher who is trained in music and music pedagogy. In 2017 a study into the effects of music instruction on the working memory of a group of four—six year olds compared memory in children learning music using the Suzuki method with those not undertaking music instruction (Hallberg, Martin and McClure, 2017). The Suzuki method was developed by Tadashi Suzuki to teach music to children from a very young age. Children as young as 19 months (Garson,1970)are given one to one instruction where they learn their instrument in a rote-learnt way by copying the adult. The Hallberg study did not find a significant difference in working memory between children learning music through the Suzuki method and those who did not receive musical instruction. Yet an earlier study (Scott, 1992) compared cognitive development in three groups of children: children undertaking music lessons through the Suzuki method, children who took part in more free-style music and movement lessons and a group who did no music. Scott found that children who took part in Suzuki style music lessons had the highest rates of attention and preserving behaviours, followed by the music and movement group.

Group learning

Another popular way young children engage with music education is in a group setting. This method may involve singing and/or instruments and possibly games. This method is usually delivered with a musically trained educator to a small or large group of children. Dena Register (2004) wrote a doctoral thesis that compared live music education with an educational television program that made some use of music. The live music education aspect was a group-based activity making use of singing, movement and instruments in line with a music therapy approach. This thesis was about the effects music has on language development and again there were some documented improvements in development for the children given the music instruction. Kate Williams published a study in 2019 which focused on the self-regulation benefits of music, rather than cognitive function. In this study children undertook a purpose-designed 30 minute ‘rhythm and music program’ twice a week. These music classes focused on behaviour and general music concepts through group based instructional musical games (Williams, 2018). This study found some improvements to the children’s ability to self-regulate. An interesting and unique part of this study is that they measured ‘child enjoyment’ (Williams, 2018). Childhood should be about having fun. If we look back to what the first kindergarten was about, it was about play and enjoyment. Friedrich Frobel designed his ‘children’s garden’ so children learnt as they played (Ahmetoğlu & Gokcen, 2018).

Embedded in curriculum

The other way children learn music is via their early childhood teacher as part of the wider curriculum. While there has been less research done on the benefits that come from this type of more incidental music education, it is still one of the major musical influences on a young child. Early childhood teachers and educators may use music as an addition to group times or in the creation of a musical play space. Vanessa Bond (2015) observed in Reggio Emilia inspired American preschools, that children engaged in both finger songs and rhymes with teachers during group and transition times as well as within free play by using the musical instruments that were added to the play spaces. Jill Holland and Amanda Niland (2016) lament the lack of music education within the Australian early childhood education system and liken music instruction to children listening to pre-recorded music and out of tune singing by educators. Now, getting back to the point ‘does delivery matter?’

Child-led, happiness focused

I am a musician and an early childhood teacher and have taught music to babies and children through the early years and beyond. Some of the methods of teaching I use are one-to-one classical instrumental lesson with rote-learnt scales, and groups using a wide variety of instruments, games and dancing with a focus on musical concepts. Other approaches I found work well are teaching music in transitional group moments, making use of finger songs and rhymes as part of a language or settling technique; and creating music play spaces, filled with instruments and sometimes a stage, where children are free to participate in pure uninterrupted play. My early childhood education practice benefits from formal musical training and hopefully, after years at university studying music, I like to think I sing in tune. But over the years there is one outcome to music that I hold above the rest: happiness. It is a little cliché, but whether from the direct interaction with music or the biproduct, my main aim in using and teaching music is for the happiness, joy and contentment of the children in my practice and my teaching style changes to suit what the child needs.

Approaches in practice

One of my early experiences involved sitting down in the baby space and pulling out my ukulele. I had discussed with the educators beforehand to let the babies to join me without being interrupted. When I started to play and sing a soft song, the babies slowly noticed the music. Some stared and some of the older ones started to crawl over to me. An educator tried to stop the baby but I asked to let the child join me. The baby sat in my lap and placed a hand on my ukulele, and after a while explored the strings, muting half the strings as I sing. But that didn’t matter, I wasn’t putting on a show, I was sharing music and that’s how very young children participate. They showed curiosity and interest by reaching out to explore. When I was singing, I noticed a few of the older babies wanted to have a turn exploring my ukulele, I put the ukulele in the middle of the floor and gently encouraged them to take turns. And next time I made sure to have enough ukuleles for all the children to explore.

When working with pre-schoolers I incorporate weekly group music lessons into the curriculum. With one particular group, we were slowly exploring rhythm, dynamics and non-traditional notation using a wide variety of instruments on rotation. The children started to add music into their everyday play, especially singing. So I set up a stage with sparkly black material on the wall and placed a covered pallet underneath. Next to the stage there was a basket of colourful scarves, two microphones, a tambourine a ukulele and four chairs, which apparently was not enough. The pre-schoolers added more chairs and created the most wonderous performances, individual and group, singing and dancing.

Children thrive and learn through fun, play, mess and music. Current practice in early childhood education in Australia promotes play-based learning and the EYLF (2009) specifically addresses children’s happiness. Music education is integral to this. Music needs to be fun! It needs to bring joy, happiness and contentment. We know music is important and aids in the whole child’s development. It should not matter how a child experiences and learns music as long as the music is fun and meaningful to that child. Some children will thrive with one to one instrumental instruction while others will enjoy simply playing with music. As educators and teachers, we can use our knowledge of each child and our ‘whole of child’ understanding of them to recognise which form of music learning will suit them and then support them to find that pathway. Early childhood music education does matter, and one thing I’ve learnt is the method matters less than the joy.

Amy Rothe is an early childhood teacher and musician. Amy started her career in classical music but quickly transferred to early childhood music education. She taught early childhood music for many years across the ACT and surrounding regional NSW. In 2019 she gained her early childhood teaching Graduate Diploma and now teaches main-stream early childhood education across two small early learning centres in the ACT. Amy strongly advocates for music in early childhood education.

References

- Bond, V. (2015). Sounds to Share: The State of Music Education in Three Reggio Emilia-Inspired North American Preschools. Journal of Research in Music Education, 62(4), 462-484. Retrieved May 24, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/43900270

- Ahmetoğlu, E. and Gokcen, I. I. (2018). The Friedrich Froebel Approach. In R. Efe, I. Koleva and E. Atasoy (Eds.) Recent Researches in Education. pp.355-366. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Collins, A. (2020) Music education helps improve children;s ability to learn. ABC Education. Tuesday 28thApril, 2020. Retrieved from: https://education.abc.net.au/newsandarticles/blog/-/b/2974240/music-education-helps-improve-children-s-ability-to-learn

- EYLF (2009) refers to Belonging, Being and Becoming. The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia(Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace, 2009

- Garson, A. (1970). Learning with Suzuki: Seven Questions Answered. Music Educators Journal, 56(6), 64-154. Retrieved May 24, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/3392719

- Holland, J. and Niland, A. (2016, July) Meaning Musical Beginnings: Bringing Music into the Curriculum and Culture of Early Childhood Education and Care. Paper presented at the meeting of the Proceedings of the 17th International Seminar of the ISME Commission on Early Childhood Music Education Ede, The Netherlands.

- Register D. (2004). The effects of live music groups versus an educational children’s television program on the emergent literacy of young children. Journal of music therapy, 41(1), 2–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/41.1.2

- Stamou, L. (2002). Plato and Aristotle on Music and Music Education: Lessons From Ancient Greece. International Journal of Music Education, os–39(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/025576140203900102

- Scott, L. (1992). Attention and Perseverance Behaviors of Preschool Children Enrolled in Suzuki Violin Lessons and Other Activities. Journal of Research in Music Education, 40(3), 225-235. Retrieved May 24, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/3345684

- Williams KE, (2018) Moving to the beat: Using music, rhythm, and movement to enhance self-regulation in early childhood classrooms, International Journal of Early Childhood p85-100

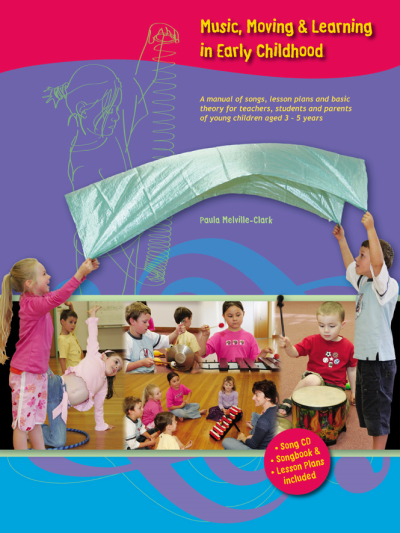

Music, Moving and Learning in Early Childhood

By Paula Melville-Clark

Music, Moving & Learning in Early Childhood looks at the fundamental theory and practice behind guiding the musical development of children ages 3 – 5 years. Written in simple terms, the book is ideally suited to early childhood teachers, students and parents. It contains information on many areas relating to music and movement, lesson plans for a years teaching and over 60 original songs and chants with CD. Purchase your copy on the ECA Shop here.

This is absolutely beautiful and inspiring. I teach music in early childhood and find that it brings so much joy to the children. I am forever researching and learning new techniques and new songs to bring to the children and would love to collaborate knowledge and practices with other early childhood teachers and educators. Amy, thank you for sharing and would love to know more about what you do.

Thanks for your comment Kelly. It’s great to hear about your own goals and practice.

Wonderful read and I do agree with you music is a great way for child to release stress and enjoy themselves. Without using technology how could I introduce mix in my room with me not been a music teacher or knkw much about music.

Hi I don’t have a musical background and sadly can’t play an instrument. But I love to sing with my 3-4 year olds. I bring out the instruments which always creates a lot of interest. How can I enrich these experiences in my early childhood setting?